Cervical Cancer: Risk Factors, Screening, Prevention and Diagnosis

Introduction: Uterine Cervix, Precancerous Lesions, Statistics, Risk Factors, Screening, Prevention and Diagnosis.

Cervical cancer ranks third in cancer incidence worldwide and is the most frequent gynecological cancer in developing countries. The frequency of cervical cancer after treatment for dysplasia is lower than 1% and mortality is less than 0.5%.

The increasing trend of the disease in developing countries is attributed to the early beginning of sexual activities, certain sexual behaviors like a high number of multiple partners, early age at first intercourse, infrequent use of condoms, and immunosuppression with HIV, which is related to a higher risk of HPV infection.

It is estimated that 10-15% of women have oncogenic HPV types (HPV high risk: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 69, 82 and HPV low risk: 6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 72, 81). In the USA, 16 and 18 types are detected in 70% of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL) as well as in invasive cervical cancer cases.

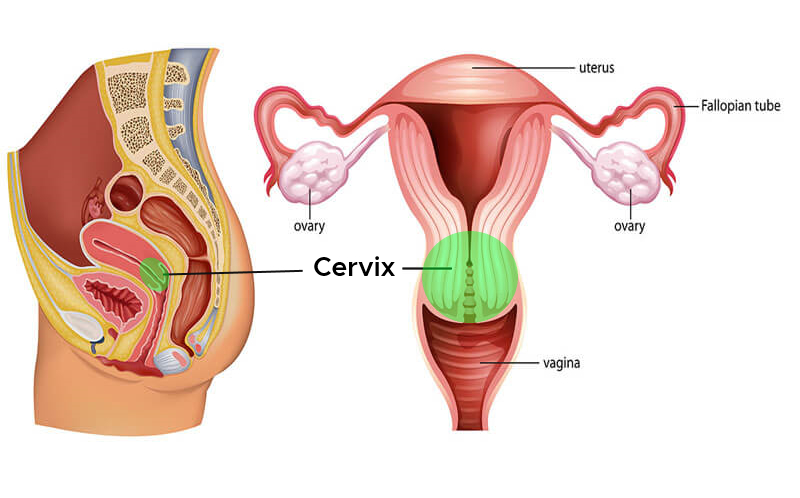

Cervical cancer starts in the cervix, which is the lower, narrow part of the uterus. The uterus holds the growing fetus during pregnancy. The cervix connects the lower part of the uterus to the vagina and, with the vagina, forms the birth canal.

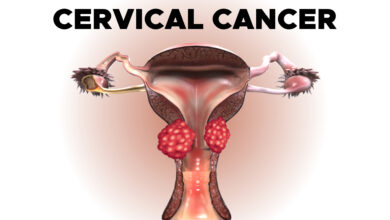

Pre-Cancers of The Cervix

Cervical cancer begins when healthy cells on the surface of the cervix change or get infected with human papillomavirus (HPV) and grow out of control, forming a mass called a tumor. Long-term infection of HPV on the cervix can result in cancer, leading to a mass or tumor on the cervix.

A tumor can be cancerous or benign. A cancerous tumor is malignant, meaning it can spread to other parts of the body. A benign tumor means the tumor will not spread.

At first, the changes in a cell are abnormal, not cancerous, and are sometimes called “atypical cells.” Researchers believe that some of these abnormal changes are the first step in a series of slow changes that can lead to cancer.

Some of the atypical cells go away without treatment, but others can become cancerous. This phase of the precancerous disease is called cervical dysplasia, which is an abnormal growth of cells. Sometimes, the dysplasia tissue needs to be removed to stop cancer from developing.

Often, the dysplasia tissue can be removed or destroyed without harming healthy tissue, but in some cases, a hysterectomy is needed to prevent cervical cancer. A hysterectomy is the removal of the uterus and cervix.

Treatment of a lesion, which is a precancerous area, depends on the following factors:

- Size of the lesion and the type of changes that have occurred in the cells

- The desire to have children in the future

- Age

- General health

- Preferences of the patient and the doctor

If the precancerous cells change into cancer cells and spread deeper into the cervix or to other tissues and organs, then the disease is called cervical cancer or invasive cervical cancer.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer can grow from the surface of the cervix seen in the vagina, called the ectocervix, or from the canal going from the vagina to the uterus, called the endocervix.

There are 2 main types of cervical cancer named for the type of cell where cancer started. Other types of cervical cancer are rare.

- Squamous cell carcinoma makes up about 80% to 90% of all cervical cancers. These cancers start in the cells on the outer surface covering the cervix.

- Adenocarcinoma makes up 10% to 20% of all cervical cancers. These cancers start in the glandular cells that line the lower birth canal in the internal portion of the cervix.

The squamous and glandular cells meet at the opening of the cervix at the squamocolumnar junction, which is the location at which most cervical cancers start.

Statistics of Cervical Cancer

Incidence rates of cervical cancer dropped by more than 50% from the mid-1970s to the mid-2000s due in part to an increase in screening, which can find cervical changes before they turn cancerous. Decreasing incidence rates in young women may be due to the use of the HPV vaccine.

It is estimated that 4,290 deaths from cervical cancer will occur this year. Similar to the incidence rates, the death rate dropped by around 50% since the mid-1970s, partly because the increase in screening resulted in earlier detection of cervical cancer. However, the decrease in the death rate has gone from around 4% each year from 1996 to 2003 to less than 1% from 2009 to 2018.

Cervical cancer is most often diagnosed between the ages of 35 and 44. The average age of diagnosis is 50. About 20% of cervical cancers are diagnosed after age 65. Usually, these cases occur in people who did not receive regular cervical cancer screenings before age 65. It is rare for people younger than 20 to develop cervical cancer.

The 5-year survival rate tells you what percent of people live at least 5 years after the cancer is found. Percent means how many out of 100. The 5-year survival rate for all people with cervical cancer is 66%.

However, survival rates can vary by factors such as race, ethnicity, and age. For white women, the 5-year survival rate is 71%. For Black women, the 5-year survival rate is 58%. For white women younger than age 50, the 5-year survival rate is 78%. For Black women age 50 and older, the 5-year survival rate is 46%.

Survival rates depend on many factors, including the stage of cervical cancer that is diagnosed. When detected at an early stage, the 5-year survival rate for people with invasive cervical cancer is 92%. About 44% of people with cervical cancer are diagnosed at an early stage.

It is important to remember that statistics on the survival rates for people with cervical cancer are an estimate. The estimate comes from annual data based on the number of people with this cancer in the United States.

Also, experts measure the survival statistics every 5 years. So the estimate may not show the results of better diagnosis or treatment available for less than 5 years. Talk with your doctor if you have any questions about this information.

Risk Factors of Cervical Cancer

A risk factor is anything that increases a person’s chance of developing cancer. Although risk factors often influence the development of cancer, most do not directly cause cancer.

Some people with several risk factors never develop cancer, while others with no known risk factors do. Knowing your risk factors and talking about them with your doctor may help you make more informed lifestyle and health care choices.

The following factors may raise a person’s risk of developing cervical cancer:

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The most important risk factor for cervical cancer is infection with HPV. HPV is common. Most people become infected with HPV when they become sexually active, and most people clear the virus without problems. There are over 100 different types of HPV. Not all of them are linked to cancer. The HPV types, or strains, that are most frequently associated with cervical cancer are HPV16 and HPV18. Starting to have sex at an earlier age or having multiple sexual partners puts a person at a higher risk of being infected with high-risk HPV types.

- Immune system deficiency. People with lowered immune systems have a higher risk of developing cervical cancer. A lowered immune system can be caused by immune suppression from corticosteroid medications, organ transplantation, treatments for other types of cancer, or from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which is the virus that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). When a person has HIV, their immune system is less able to fight off early cancer.

- Women who have genital herpes have a higher risk of developing cervical cancer.

- Women who smoke are about twice as likely to develop cervical cancer as women who do not smoke.

- People younger than 20 years old rarely develop cervical cancer. The risk goes up between the late teens and mid-30s. Women past this age group remain at risk and need to have regular cervical cancer screenings, which include a Pap test and/or an HPV test.

- Socioeconomic factors. Cervical cancer is more common among groups of women who are less likely to have access to screening for cervical cancer. Those populations are more likely to include Black women, Hispanic women, American Indian women, and women from low-income households.

- Oral contraceptives. Some research studies suggest that oral contraceptives, which are birth control pills, may be associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer and may be associated with higher-risk sexual behavior. However, more research is needed to understand how oral contraceptive use and the development of cervical cancer are connected.

- Exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES). Women whose mothers were given this drug during pregnancy to prevent miscarriage have an increased risk of developing a rare type of cancer of the cervix or vagina. DES was given for this purpose from about 1940 to 1970. Women exposed to DES should have an annual pelvic examination that includes a cervical Pap test as well as a 4-quadrant Pap test, in which samples of cells are taken from all sides of the vagina to check for abnormal cells.

Research continues to look into what factors cause this type of cancer, including ways to prevent it and what people can do to lower their personal risk.

There is no proven way to completely prevent this disease, but there may be steps you can take to lower your cancer risk. Talk with your health care team if you have concerns about your personal risk of developing cervical cancer.

Screening and Prevention of Cervical Cancer

A. Prevention

Cervical cancer can often be prevented by having regular screenings with Pap tests and HPV tests to find any precancers and treat them. It can also be prevented by receiving the HPV vaccine.

The HPV vaccine Gardasil is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of cervical cancer caused by HPV for people between ages 9 and 45. Gardasil 9 is available in the United States for preventing infection from HPV16, HPV18, and 5 other types of HPV linked with cancer.

There were 2 other vaccines previously available in the United States: Cervarix and the original Gardasil. However, because of newer vaccines becoming available, these 2 are no longer available in the United States. However, these vaccines may still be in use outside of the United States.

To help prevent cervical cancer, ASCO recommends that girls receive the HPV vaccination. Talk with a health care provider about the appropriate schedule for vaccination as it may vary based on many factors, including age, gender, and vaccine availability.

Additional actions people can take to help prevent cervical cancer include:

- Delaying first sexual intercourse until the late teens or older

- Limiting the number of sex partners

- Practicing safe sex by using condoms and dental dams

- Avoiding sexual intercourse with people who have had many partners

- Avoiding sexual intercourse with people who are infected with genital warts or who show other symptoms

- Quitting smoking

B. Screening Information for Cervical Cancer

Screening is used to detect precancerous changes or early cancers before signs or symptoms of cancer occur. Scientists have developed, and continue to develop, tests that can be used to screen a person for specific types of cancer before signs or symptoms appear. The overall goals of cancer screening are to:

- Reduce the number of people who die from cancer, or eliminate deaths from the cancer

- Reduce the number of people who develop the cancer

The following tests and procedures may be used to screen for cervical cancer:

- HPV test. This test is done on a sample of cells removed from the cervix, the same sample used for the Pap test. This sample is tested for the strains of HPV most commonly linked to cervical cancer. HPV testing may be done by itself or combined with a Pap test. This test may also be done on a sample of cells collected from the vagina, which women can collect on their own.

- Pap test. The Pap test has been the most common test for early changes in cells that can lead to cervical cancer. This test is also called a Pap smear. A Pap test involves gathering a sample of cells from the cervix. It is often done at the same time as a bimanual pelvic exam as part of a gynecologic checkup. A Pap test may be combined with an HPV test.

- Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA). VIA is a screening test that can be done with a few tools and the naked eye. During VIA, a dilution of white vinegar is applied to the cervix. The health care provider then looks for abnormalities on the cervix, which will turn white when exposed to vinegar. This screening test is very useful in places where access to medical care is limited.

Screening for cervical cancer can be done during an appointment with a primary care doctor or a gynecologic specialist. In some areas, free or low-cost screening may be available.

C. Screening Recommendations for Cervical Cancer

Different organizations have looked at the scientific evidence, risks, and benefits of cervical cancer screening. These groups have developed screening recommendations for women in the United States.

ASCO recommends that all women receive at least 1 HPV test to screen for cervical cancer in their lifetime. The American Cancer Society recommends that women ages 25 to 65 should receive an HPV test once every 5 years.

Women 65 and older or women who have had a hysterectomy may stop screening if their HPV test results have been mostly negative over the previous 15 years. Sometimes, women who are 65 and older and who have tested positive for HPV may continue screening until they are 70.

Decisions about screening for cervical cancer are becoming increasingly individualized. Sometimes, screening may differ from the recommendations discussed above due to a variety of factors. Such factors include your personal risk factors and your health history.

It’s important to talk with your health care team or a health care professional knowledgeable in cervical cancer screening about how often you should receive screening and which tests are most appropriate.

Here are some questions to ask a health care professional:

- At what age should I start being screened for cervical cancer?

- Should my screening include an HPV test? If so, how often?

- Why are you recommending these specific tests and this screening schedule for me?

- At what age could I stop being regularly screened for cervical cancer?

- Do any recommendations change if I have had cervical dysplasia or precancer?

- Do any recommendations change if I have HIV?

- Do any recommendations change if I have had a hysterectomy?

- Do any recommendations change if I am pregnant?

- Do any recommendations change if I have had the HPV vaccine?

- What happens if the screening shows positive or abnormal results?

All women should talk with their health care team about cervical cancer and decide on an appropriate screening schedule. For women at high risk for developing cervical cancer, screening is recommended at an earlier age and more often than for women who have an average risk of cervical cancer.

Symptoms and Signs of Cervical Cancer

Precancer often does not cause any signs or symptoms. Symptoms do typically appear with early-stage cervical cancer. With advanced cancer or cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, the symptoms may be more severe depending on the tissues and organs to which the disease has spread.

The cause of a symptom may also be a different medical condition that is not cancer, which is why people need to seek medical care if they have a new symptom that does not go away.

Any of the following could be signs or symptoms of cervical cancer:

- Blood spots or light bleeding between or following periods

- Menstrual bleeding that is longer and heavier than usual

- Bleeding after intercourse, douching, or a pelvic examination

- Increased vaginal discharge

- Pain during sexual intercourse

- Bleeding after menopause

- Unexplained, persistent pelvic and/or back pain

Any of these symptoms should be reported to your doctor. If these symptoms appear, it is important to talk with your doctor about them even if they appear to be symptoms of other, less serious conditions.

The earlier precancerous cells or cancer are found and treated, the better the chance that cancer can be prevented or cured.

If you are concerned about any changes you experience, please talk with your doctor. Your doctor will ask how long and how often you’ve been experiencing the symptom(s), in addition to other questions. This is to help figure out the cause of the problem, called a diagnosis.

If cervical cancer is diagnosed, relieving symptoms remains an important part of cancer care and treatment. This may be called palliative care or supportive care. It is often started soon after diagnosis and continued throughout treatment. Be sure to talk with your health care team about the symptoms you experience, including any new symptoms or a change in symptoms.

Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer

Doctors use many tests to find or diagnose, cancer. They also do tests to learn if cancer has spread to another part of the body from where it started. If this happens, it is called metastasis.

For example, imaging tests can show if cancer has spread. Imaging tests show pictures of the inside of the body. Doctors may also do tests to learn which treatments could work best.

For most types of cancer, a biopsy is the only sure way for the doctor to know if an area of the body has cancer. In a biopsy, the doctor takes a small sample of tissue for testing in a laboratory. If a biopsy is not possible, the doctor may suggest other tests that will help make a diagnosis.

This section describes options for diagnosing cervical cancer. Not all tests listed below will be used for every person. Some or all of these tests may be helpful for your doctor to plan the treatment of your cancer. Your doctor may consider these factors when choosing a diagnostic test:

- The type of cancer suspected

- Your signs and symptoms

- Your age and general health

- The results of earlier medical tests

The following tests may be used to diagnose cervical cancer:

- Bimanual pelvic examination and sterile speculum examination. In this examination, the doctor will check for any unusual changes in the patient’s cervix, uterus, vagina, ovaries, and other nearby organs. To start, the doctor will look for any changes to the vulva outside the body, and then, using an instrument called a speculum to keep the vaginal walls open, the doctor will look inside the vagina to visualize the cervix. A Pap test is often done at the same time. Some of the nearby organs are not visible during this exam, so the doctor will insert 2 fingers of 1 hand inside the vagina while the other hand gently presses on the lower abdomen to feel the uterus and ovaries. This exam typically takes a few minutes and is done in an examination room at the doctor’s office.

- Pap test. During a Pap test, the doctor gently scrapes the outside and inside of the cervix, taking samples of cells for testing.

- Improved Pap test methods have made it easier for doctors to find cancerous cells. Traditional Pap tests can be hard to read because cells can be dried out, covered with mucus or blood, or may clump together on the slide.

- The liquid-based cytology test, often referred to as ThinPrep or SurePath, transfers a thin layer of cells onto a slide after removing blood or mucus from the sample. The sample is preserved so other tests can be done at the same time, such as the HPV test.

- Computer screening, often called AutoPap or FocalPoint, uses a computer to scan the sample for abnormal cells.

- HPV typing test. An HPV test is similar to a Pap test. The test is done on a sample of cells from the cervix. The doctor may test for HPV at the same time as a Pap test or after Pap test results show abnormal changes to the cervix. Certain types or strains of HPV, called high-risk HPV, such as HPV16 and HPV18, are seen more often in women with cervical cancer and may help confirm a diagnosis. If the doctor says the HPV test is “positive,” this means the test found the presence of high-risk HPV. Many women have HPV but do not have cervical cancer, so HPV testing alone is not enough for a diagnosis of cervical cancer.

- The doctor may do a colposcopy to check the cervix for abnormal areas. Colposcopy can also be used to help guide a biopsy of the cervix. During a colposcopy, a special instrument called a colposcope is used. The colposcope magnifies the cells of the cervix and vagina, similar to a microscope. It gives the doctor a lighted, magnified view of the tissues of the vagina and the cervix. The colposcope is not inserted into the body, and the examination is similar to a speculum examination. It can be done in the doctor’s office and has no side effects. It can also be done on pregnant women.

- A biopsy is the removal of a small amount of tissue for examination under a microscope. Other tests can suggest that cancer is present, but only a biopsy can make a definite diagnosis. A pathologist then analyzes the sample(s). A pathologist is a doctor who specializes in interpreting laboratory tests and evaluating cells, tissues, and organs to diagnose disease. If the lesion is small, the doctor may remove all of it during the biopsy.

- There are several types of biopsies. Most are usually done in the doctor’s office, sometimes using a local anesthetic to numb the area. There may be some bleeding and other discharge after a biopsy. There may also be discomfort similar to menstrual cramps. One common biopsy method uses an instrument to pinch off small pieces of cervical tissue. Other types of biopsies include:

- Endocervical curettage (ECC). If the doctor wants to check an area inside the opening of the cervix that cannot be seen during a colposcopy, they will use ECC. During this procedure, the doctor uses a small, spoon-shaped instrument called a curette to scrape a small amount of tissue from inside the cervical opening.

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). LEEP uses an electrical current passed through a thin wire hook. The hook removes tissue for examination in the laboratory. A LEEP may also be used to remove a precancer or early-stage cancer.

- Conization (a cone biopsy). This removes a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. Conization may be done as treatment to remove a precancer or early-stage cancer. It is done under a general or local anesthetic and may be done in the doctor’s office or the hospital.

If the biopsy shows that cervical cancer is present, the doctor will refer you to a gynecologic oncologist, which is a doctor who specializes in treating this type of cancer. The specialist may suggest additional tests to see if cancer has spread beyond the cervix.

- Pelvic examination under anesthesia. In cases where it is necessary for treatment planning, the specialist may re-examine the pelvic area while the patient is under anesthesia to see if cancer has spread to any organs near the cervix, including the uterus, vagina, bladder, or rectum.

- X-ray. An x-ray is a way to create a picture of the structures inside of the body using a small amount of radiation. An intravenous urography is a type of x-ray that is used to view the kidneys and bladder.

- Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan. A CT scan takes pictures of the inside of the body using x-rays taken from different angles. A computer combines these pictures into a detailed, 3-dimensional image that shows any abnormalities or tumors. A CT scan can be used to measure the tumor’s size. Sometimes, a special dye called a contrast medium is given before the scan to provide better detail on the image. This dye can be injected into a patient’s vein or given as a pill or liquid to swallow.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses magnetic fields, not x-rays, to produce detailed images of the body. MRI can be used to measure the tumor’s size. A special dye called a contrast medium is given before the scan to create a clearer picture. This dye can be injected into a patient’s vein or given as a pill or liquid to swallow.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) or PET-CT scan. A PET scan is usually combined with a CT scan, called a PET-CT scan. However, you may hear your doctor refer to this procedure just as a PET scan. A PET scan is a way to create pictures of organs and tissues inside the body. A small amount of a radioactive sugar substance is injected into the patient’s body. This sugar substance is taken up by cells that use the most energy. Because cancer tends to use energy actively, it absorbs more of the radioactive substance. A scanner then detects this substance to produce images of the inside of the body.

- Molecular testing of the tumor. Your doctor may recommend running laboratory tests on a tumor to identify specific genes, proteins, and other factors unique to the tumor. Results of these tests can help determine your treatment options.

If there are signs or symptoms of bladder or rectal problems, these procedures may be recommended and may be performed at the same time as a pelvic examination:

- A cystoscopy is a procedure that allows the doctor to view the inside of the bladder and urethra (the canal that carries urine from the bladder) with a thin, lighted tube called a cystoscope. The person may be sedated as the tube is inserted into the urethra. A cystoscopy is used to determine whether cancer has spread to the bladder.

- Sigmoidoscopy (also called a proctoscopy). A sigmoidoscopy is a procedure that allows the doctor to see the colon and rectum with a thin, lighted, flexible tube called a sigmoidoscope. The person may be sedated as the tube is inserted into the rectum. A sigmoidoscopy is used to see if cancer has spread to the rectum.

After diagnostic tests are done, your doctor will review all of the results with you. If the diagnosis is cervical cancer, these results also help the doctor describe cancer. This is called staging.