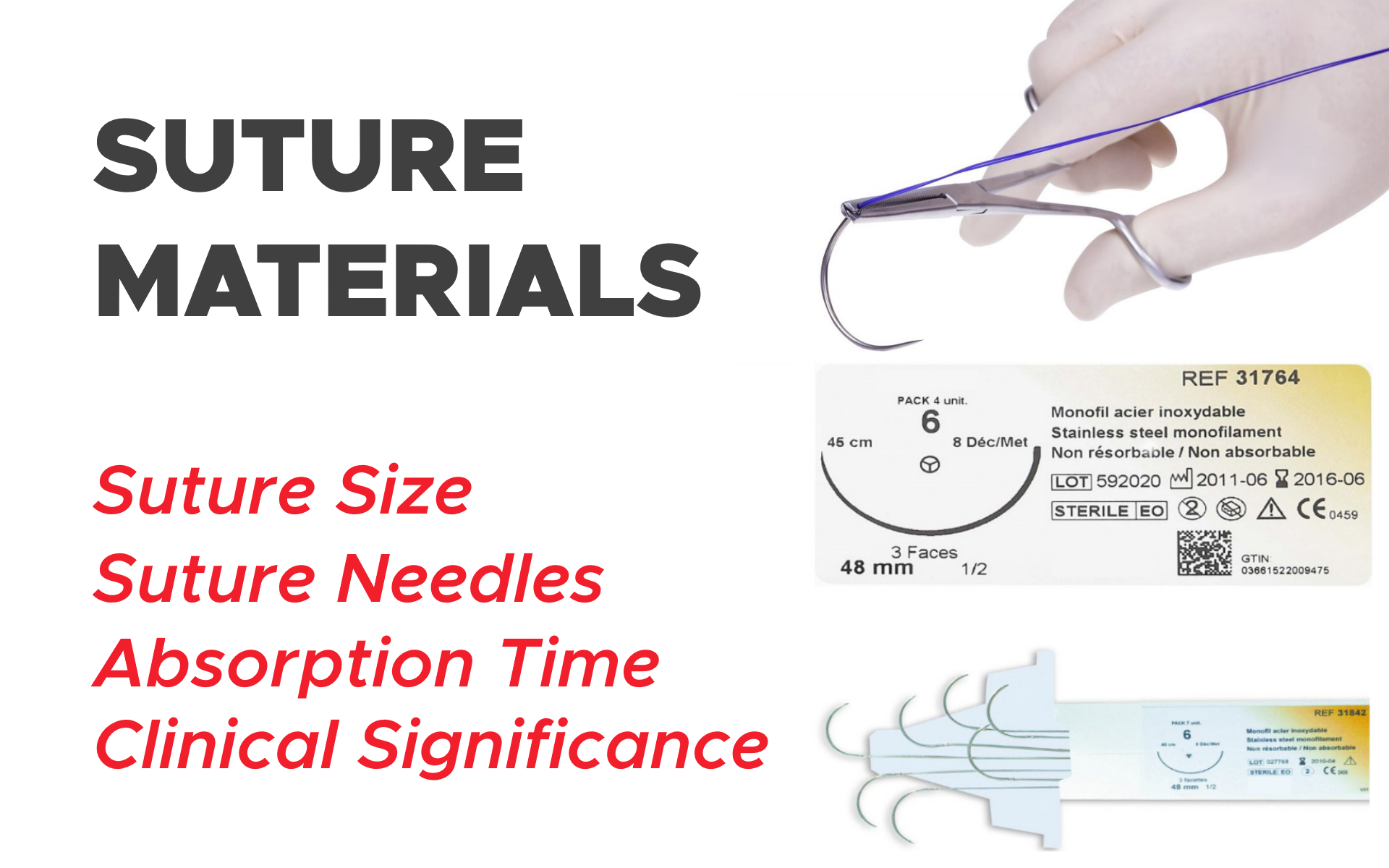

Suture Materials: Suture Size, Absorption Time, Suture Needles and Clinical Significance

There is no specific algorithm for suture choice; however, a few rules are helpful.

Suture Material

Choice of appropriate suture material and its gauge is dependent on the anatomical location of the wound, the tissue type to be sutured, the tension of the tissue, and the length of time the suture is to remain in situ for proper healing of the wound.

Smaller gauges of suture offer less trauma to the tissue but are more delicate; knots should be tied gently but firmly to prevent breakage of the suture material.

Suture material may be absorbable or non-absorbable, synthetically produced or natural, and may be mono or multi-filament. Each will have differing tensile strengths which deteriorate over time. All of these factors should be taken into account when choosing a suture material.

a. Monofilament Materials:

Monofilament materials are made up of a single fiber; multifilament materials consist of more than one fiber that is twisted together.

Monofilament materials (and coated materials) provide less tissue drag than multifilament, so are generally less traumatic to the tissue.

b. Multifilament Materials:

Multifilament suture material is usually more pliable than monofilament and has less memory, making it easier to handle and provides better knot security.

A ‘wicking’ effect, however, occurs with multifilament material, making it inappropriate for use in certain situations (such as for skin closure) where it may draw bacteria into the wound from the external environment.

| Suture name/brand | Material | Natural or synthetic | Absorbable or non-absorbable | Construction | Tensile strength | Time of absorption |

| Fast-Abs Gut (Ethicon) | Beef serosa/sheep submucosa | Natural | Absorbable | Monofilament | 5–7 days | 21–42 days |

| Plain Gut (Ethicon) | Beef serosa/sheep submucosa | Natural | Absorbable | Monofilament | 7–10 days | 70 days |

| Chromic Gut (coated) (Ethicon) | Beef serosa/sheep submucosa | Natural | Absorbable | Monofilament | 21–28 days | 90 days |

| Vicryl Rapide (Ethicon) | Polyglactin 910 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Multifilament | 50% at 5 days 40% at 14 days | 42 days |

| Monocryl (undyed) (Ethicon) | Poliglecaprone 25 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 55% at 7 days 30% at 14 days | 91–119 days |

| Monocryl (dyed) (Ethicon) | Poliglecaprone 25 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 65% at 7 days 35% at 14 days | 91–119 days |

| Vicryl (Ethicon) | Polyglactin 910 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Multifilament | 75% at 14 days 50% at 21 days 25% at 28 days | 56–70 days |

| PDS II (Ethicon) | Polydioxanone | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 70% at 14 days 50% at 28 days 25% at 42 days | 180–210 days |

| Silk (Ethicon) | Silk | Natural | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | 1 year | N/A |

| Steel (Ethicon) | 316L Stainless Steel | Natural | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Ethilon (Ethicon) | Nylon 6 | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | 20% loss per year | N/A |

| Nurolon (Ethicon) | Nylon 6 | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | 20% loss per year | N/A |

| Mersilene (Ethicon) | Polyester/Dacron | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Ethibond Excel (Ethicon) | Polyester/Dacron | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Prolene (Ethicon) | Polypropolene | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Polysorb (Covidien) | Lactomer 9-1 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Braided | 21 days | 56–70 days |

| Caprosyn (Covidien) | Polyglytone 6211 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 10 days | 56 days |

| Biosyn (Covidien) | Glycomer 631 | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 21 days | 90–110 days |

| Maxon (Covidien) | Polyglyconate | Synthetic | Absorbable | Monofilament | 42 days | 180 days |

| Surgipro II (Covidien) | Polyprolene | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Monosof (Covidien) | Nylon | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Dermalon (Covidien) | Nylon | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Novafil (Covidien) | Polybutester | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Monofilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Sofsilk (Covidien) | Silk | Natural | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | Indefinite | N/A |

| Ti-Cron (Covidien) | Polyester | Synthetic | Non-absorbable | Multifilament | Indefinite | N/A |

The most commonly used in practice are poliglecaprone 25, polyglactin, polydioxanone, and polypropolene. An antibacterial version of Vicryl, Monocryl and PDS II have been produced which are coated with triclosan and offer increased resistance to infection.

A study comparing suture materials with and without a triclosan coating showed a 30% reduction in post-operative infection when a triclosan coated suture was used in clean and clean-contaminated surgical wounds.

Natural suture materials are absorbed via enzymatic degradation, and synthetic suture materials are absorbed via hydrolysis.

Catgut can cause a severe inflammatory reaction within the tissue, due to its unpredictability of absorption, whereas synthetic materials have a much more predictable pattern of absorption which is not affected by an inflamed or infected wound.

Suture Size

The gauge of suture material is given by two measures: The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and metric. Both are defined by the size of the suture in millimeters, for example, a 0.2 mm suture would be either 2 (in metric) or 3–0 (in USP), and a 0.3 mm suture would be size 3 in metric or 2–0 in USP (as shown in below).

The size of suture chosen should be at least as strong as the tissue it is to hold together, but the smallest possible size to prevent excessive tissue trauma and reduce inflammatory reaction. The tensile strength should last for as long as the wound is likely to take to heal fully.

Comparison of measurement systems for suture materials

| Size in mm | Metric Gauge | USP Gauge for Synthetic Materials |

| 0.02 | 0.2 | 10–0 |

| 0.03 | 0.3 | 9–0 |

| 0.04 | 0.4 | 8–0 |

| 0.05 | 0.5 | 7–0 |

| 0.07 | 0.7 | 6–0 |

| 0.1 | 1 | 5–0 |

| 0.15 | 1.5 | 4–0 |

| 0.2 | 2 | 3–0 |

| 0.3 | 3 | 2–0 |

| 0.35 | 3.5 | 0 |

| 0.4 | 4 | 1 |

| 0.5 | 5 | 2 |

| 0.6 | 6 | 3, 4 |

| 0.7 | 7 | 5 |

| 0.8 | 8 | 6 |

| 0.9 | 9 | 7 |

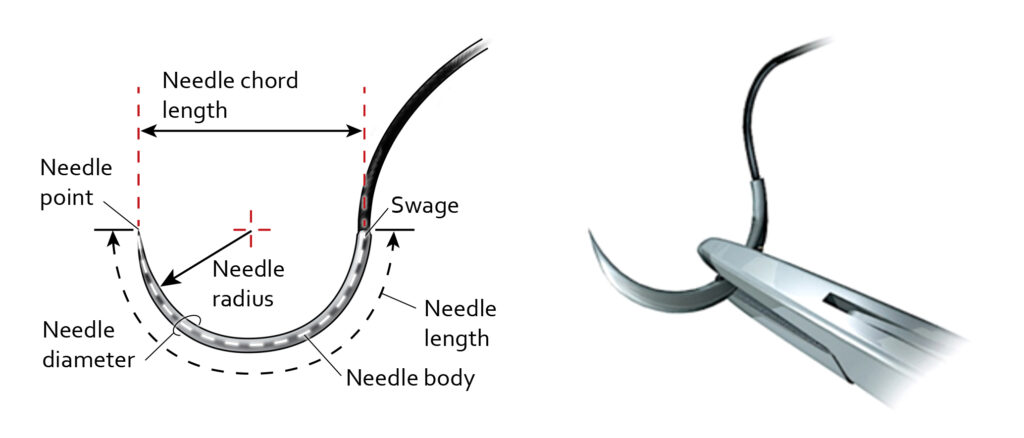

Suture Needles

An appropriate needle should be chosen based on the tissue type being sutured, to minimize trauma and prevent a delayed wound healing time. Needles are available in a variety of lengths, gauges, and shapes and are also described by the taper type.

Needles may be either swaged-on (attached to the suture material) or non-swaged (have an eye for passing the suture material through).

Swaged needles are less traumatic to the tissue than eyed needles, as there is no doubling up of the suture material as there would be in an un-swaged needle when it passes through the needle eye.

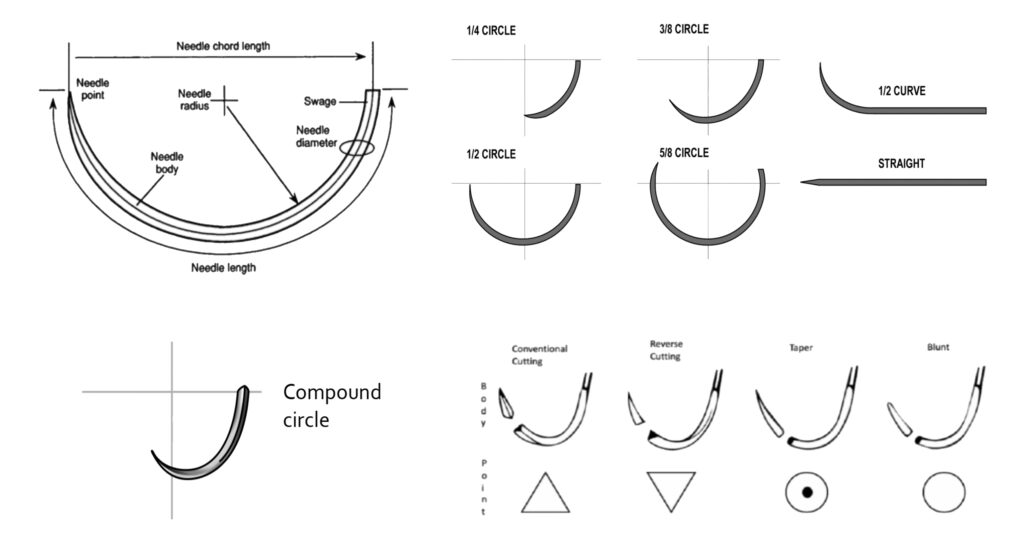

The shape of the needle used is defined by the amount of space the surgeon has to manipulate the needle through the tissue. Straight needles are generally used near the surface of the skin where there is more space for hand motion.

Curved needles may also be used at the surface, due to ease of passing the suture material, but they are excellent for use when suturing internal tissues in a smaller or deeper area, as the hand motion required is reduced to a mere twist of the wrist to push the needle through.

Needles differ in length and for curved needles, the fraction of a circle is also defined. J needles are a combination of both straight and curved needles and can be used close to the skin surface.

Needles may be cutting or non-cutting. Cutting needles are usually triangular and have two or three cutting edges. They are used for passing through tougher tissues, such as skin. They may be taper-cut, regular cutting, reverse cutting, or spatula point.

Reverse cutting is used most often as they are stronger than cutting needles and cause minimal tissue trauma; there is a third cutting edge on the outer curvature of the needle which allows easy penetration of the tissues.

Clinical Significance

While there are many properties to sutures, it is most important to be able to determine which sutures are best for individual clinical scenarios.

This determination depends on the thickness and location of the tissues, the amount of tension across the wound, and the risk of infection. One needs to choose the caliber, type of filament (absorbable or non-absorbable), and the tissue and needle needs.

There is no specific algorithm for suture choice; however, a few rules are helpful. For instance, if there is a high infection risk, a monofilament absorbable suture is chosen. For running intradermal sutures, thin monofilament absorbable sutures with minimal reactivity are typically used.

When suturing the skin, particularly in cosmetically sensitive areas, the smallest suture for the area should be used.

Trials have shown no major differences between absorbable and non-absorbable sutures in terms of cosmesis and complications, scars, and patient satisfaction. For absorbable sutures, if more strength is required, choose a suture with a longer absorption time.

Slow healing tissues, like fascia and tendons, should be closed with non-absorbable or slow absorbing sutures. While faster healing tissues like the stomach, colon, and bladder require absorbable sutures.

Urinary and biliary tracts are prone to stone formation, so synthetic absorbable sutures are better in this situation, while sutures prone to digestive juices should be those that last longer.

Natural sutures do very badly in the GI tract. A non-absorbable suture is best when prolonged tension (fascial closure, tendon repair, bone anchoring, or ligament repair) is required for suitable healing to take place.

In general, surgeons typically use either polypropylene or polydioxane sutures for fascia, depending on how strong the repair needs to be.

Deep dermis closure is with either polyglycolic acid or poliglycaprone 25 sutures. If closing the epidermis with a running subcuticular suture, poliglycaprone 25 is preferred.

If one is performing interrupted sutures on the skin surface, nylon is ideal; polydioxane for near dark hair and fast absorbing or chromic gut suture if it is on a child or in an area where sutures are difficult to remove. Many good choices exist depending on provider preference, experience, and the desired result.