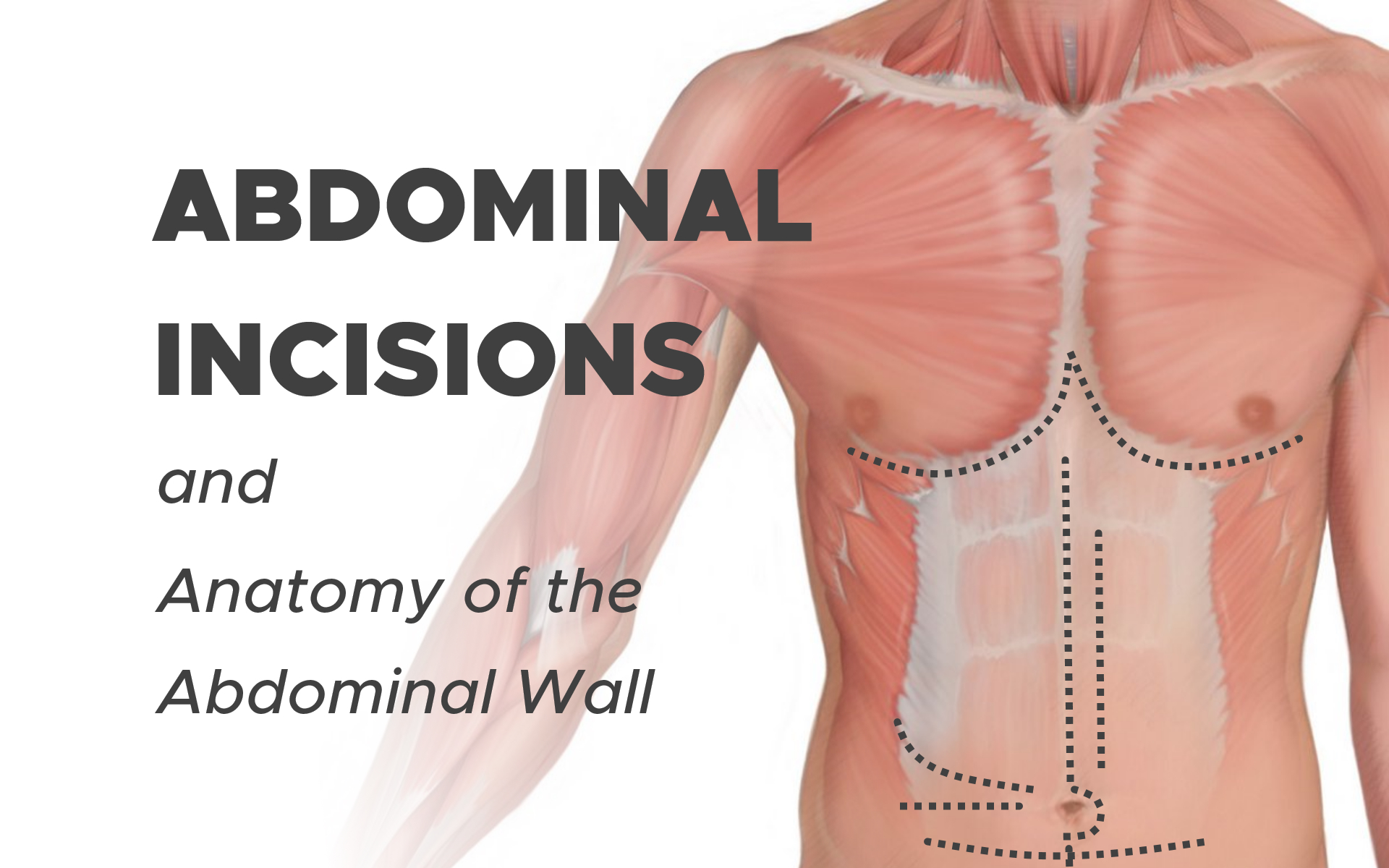

Abdominal Incisions and Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall

Types of Abdominal Incisions: Midline, Paramedian, Transverse and Oblique Incisions

The choice of abdominal incision is mainly dependent on the area that needs to be exposed, the elective or emergency nature of the operation and the surgeon’s personal preference. However, type of abdominal incision may have a profound influence on the occurrence of postoperative wound complications.

Considering the number of laparotomies performed (e.g. 4.000.000 in the USA annually), consequences of the use of a specific type of abdominal incision may be substantial.

Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall

The external oblique muscle originates from the 5th to 12th ribs and has a medio-caudal direction. The internal oblique muscle originates from the iliac crest and follows a medio-proximal direction.

The direction of the fibres of both muscles rarely deviates more than 30° from the horizontal. The transverse muscle originates from the lower six ribs, the lumbodorsal fascia and the iliac crest. Its fibres are directed horizontally.

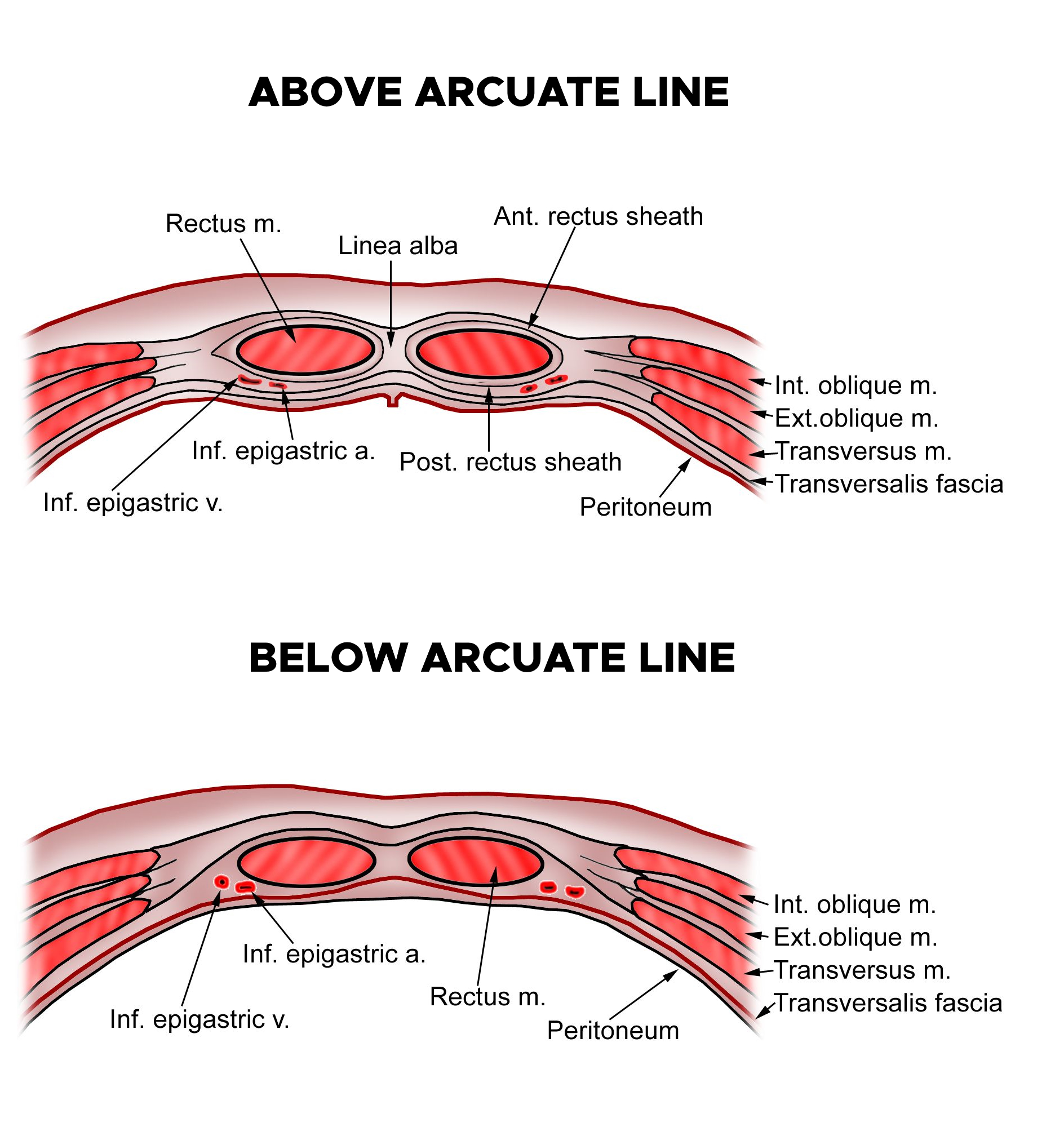

The aponeuroses of these three muscles form the sturdy rectus sheaths, which enclose the fourth abdominal wall muscle, the rectus abdominis, which inserts on the 5th, 6th and 7th ribs superiorly and on the pubic bone inferiorly.

The rectus sheath may be considered as having three distinct sections:

1) For most of the length of the paired recti, the anterior sheath is formed by the external oblique and anterior leaf of the internal oblique aponeuroses. The recti are interrupted by three paired tendinous intersections anchoring them to the anterior sheath, broadly found close to the xiphisternum, at the level of the umbilicus and then halfway between the two.

The posterior sheath is formed by the posterior leaf of the internal and the transversus abdominis aponeuroses and bears the superior and inferior epigastric arteries and their anastomotic network.

The aponeurotic components of the sheath interdigitate in a thickened fibrous midline raphe between the two recti known helpfully as the linea alba (‘white line’). An elastic defect in this raphe may allow the fascia to stretch and abdominal contents to bulge forward through the resulting divarication of the recti.

This produces a distinct ridge in the midline on increasing intra-abdominal pressure that is often mistaken for an epigastric hernia.

Point defects in the aponeurotic intersections of the linea alba may facilitate the development of epigastric hernias, which often simply contain preperitoneal fat but are often disproportionately painful for their size owing to their high tendency to strangulate.

2) There is no posterior sheath above the level of the costal margin, as the recti remain covered anteriorly by the external oblique aponeurosis and insert directly onto the underlying costal cartilages.

3) Roughly one third to halfway between the umbilicus and the pubic symphysis lies the arcuate Line (of Douglas), which is the point at which the posterior elements of the sheath perforate to join the anterior sheath and leave the thickened transversalis fascia in direct contact with the rectus muscles.

The sheath is bounded laterally by the Linea Semilunaris, which is the longitudinal margin at which the internal oblique aponeuroses bifurcate to form anterior and posterior leaves. Defects in the integrity of the internal oblique may give rise to the formation of Spigellian Hernias, allowing protrusion of the peritoneal sac into the rectus sheath.

On examination, the patient may have a palpable lump close to the lateral border of the rectus sheath, commonly at the level of Douglas. The superficial nature of these hernias makes them amenable to diagnosis by ultrasonography.

In between both muscles the rectus sheaths join to form the relatively avascular linea alba. The fibre direction within the linea alba is equal to that of the aponeuroses of the oblique and transverse muscles: medio-proximal, medio-caudal and horizontal.

The width of the linea alba is approximately 15–20 mm above the umbilicus, 20–25 mm at the level of the umbilicus and 0–5 mm below the umbilicus. Blood supply to the abdominal wall is taken care of by two systems.

Firstly, the inferior and superior epigastric arteries form a longitudinal anastomosis, which is called the deep epigastric arcade. The arcade is situated between the rectus abdominis muscle and its posterior sheath and supplies the muscle by perforating vessels.

Some of these perforating vessels send small branches across the midline to take care of blood supply to the linea alba.

Secondly, blood supply to the oblique and transverse muscles is taken care of by transverse segmental arteries that arise from the aorta and are situated between the internal oblique and transverse muscles. These segmental arteries follow a slightly downward transverse direction.

The innervation of the abdominal wall consists of ventral branches of the 5th to 12th thoracic nerves and the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. These nerves are directed transversely with a course comparable to the course of the segmental arteries.

Superficial to the external oblique lies Scarpa’s membranous fascia, Camper’s subcutaneous fatty layer, and the skin. Deep to transversus abdominis, the transversalis fascia encircles the preperitoneal fat and parietal peritoneum.

Incisions through the anterolateral wall will, therefore, breach the following structures:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous fatty layer

- Membranous fascia

- External oblique

- Internal oblique

- Transversus abdominis

- Transversalis fascia

- Preperitoneal fat

- Parietal peritoneum

Abdominal Incisions

I. Midline Incisions

The midline incision implies a vertical incision through skin, subcutaneous fat, linea alba, and peritoneum. Most of the fibres, crossing the linea alba in a medio-caudal and medio-proximal direction, are cut transversely.

A midline incision will thus encounter the following layers of tissue:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous fatty layer (Camper’s fascia)

- Membranous fascia (Scarpa’s)

- Linea alba

- Transversalis fascia

- Preperitoneal fat

- Parietal peritoneum

The incision is easy to perform and results in minimal blood loss, because of the avascular nature of the linea alba. The incision can be made quickly, taking 7 minutes on average.

Moreover, exposure of the abdomen is excellent. Extensions, when required, can easily be made superiorly or inferiorly, providing access to the whole abdominal cavity, including the retroperitoneum. All these qualities make the midline approach especially suitable for emergency and exploratory surgery.

II. Paramedian Incisions

An alternative for the standard midline incision is the paramedian incision. This technique stays clear of the relatively avascular linea alba, possibly avoiding impaired wound healing.

Two variants are known: the conventional “medial” paramedian incision, in which the rectus sheath and rectus muscles are transected close to the linea alba, and the so-called lateral paramedian technique.

In the latter, a longitudinal incision near the lateral border of the rectus sheath is made. The rectus muscle is freed from the anterior sheath and is then retracted laterally. This lateral retraction prevents dissection of the deep epigastric arcade.

Finally, the posterior rectus sheath (above the arcuate line) and the peritoneum are opened in the same plane as the anterior rectus sheath. This technique is more complex than the midline incision, resulting in increased opening time (average 13 minutes) and blood loss.

Exposure of the abdomen is better on the side of the incision than on the contralateral side. The possibilities for extending the incision superiorly are limited by the costal margin.

III. Transverse Incisions

A supraumbilical transverse incision offers excellent exposure of the upper abdomen. However, in case the operation area needs to be enlarged, extending the original incision is more difficult than when the midline incision was used and extensions do not always offer the desired view.

When a full-length transverse incision is made, the oblique and transverse muscles, as well as the rectus abdominis muscle and linea alba are cut in a horizontal plane. The fibres of the oblique muscles are partly split and partly cut, while the transverse muscle is split along the direction of its fibres.

The rectus muscle fibres are cut perpendicular to their direction. The deep epigastric arcade is divided, but as it is supplied from above and below this should not pose a problem. Damage to the segmental arteries and nerves is minor.

The incision is accompanied by more blood loss than the midline incision and is more time-consuming (average 13 minutes).

Smaller transverse incisions can remain unilateral, take less time to perform and leave the deep epigastric arcade unharmed.

An infraumbilical transverse incision in the lower abdomen is the Pfannenstiel incision, often used for gynaecological and obstetric procedures. The skin is incised transversely, often with a convexity downward to avoid dissection of blood vessels and nerves.

The abdominal wall muscles are often cut in the same plane as the skin incision, but some surgeons open the abdominal cavity in a vertical direction, thus combining a transverse with a vertical technique.

1. Pfannenstiel’s Incisions:

These are the most common muscle-separating incisions. They are frequently used for women’s reproductive- and urinary system-related operations. They are commonly used for cesarean delivery because they provide a cosmetically better appearance. They are also known as bikini incisions. They are made just 5 cm above your groin area (pubic) and are mostly 12 cm long.

2. Cherney’s Incisions:

These are made 2-3 cm above the groin area, lower than Pfannenstiel’s incisions. They provide excellent access to the pelvic organs during urinary bladder or vaginal repair surgeries. Because they are a tendon-detaching operation, reattachment of the tendons (fibrous collagen tissue band) is tedious.

3. Maynard’s Incisions:

These are true muscle-cutting incisions. They give excellent exposure to the genital organs. They are made parallel to the traditional placement of Pfannenstiel’s incisions. They are also as popular as Pfannenstiel’s incisions for cesarean delivery and are used for cancer surgeries.

4. Modified Gibson Incisions:

These incisions are specifically made during surgeries related to women’s reproductive system or cancer surgeries. Cuts are made on the side of the midline of the abdomen (belly), most often made only on the left side.

5. Lanz Incision:

An incision designed to be more cosmetically subtle than the gridiron, with the benefit that it may be hidden beneath the bikini line but the disadvantage of commonly severing the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves.

IV. Oblique Incisions

The subcostal or Kocher incision is an oblique incision that follows the profile of the costal margin and is directed in a medio-proximal direction. It provides good exposure for biliary and bariatric surgery and can be extended bilaterally if needed.

Many segmental blood vessels and nerves are dissected, as well as the fibres of the external oblique, the transverse and the rectus abdominis muscles. The direction of the gridiron or McBurney incision is medio-caudal. It follows the direction of the fibres of the external oblique muscle, segmental blood vessels and nerves, damaging as little as possible.

Notably, this incision splits all three muscular layers parallel to the direction of their fibres. Time to perform the incision and blood loss are comparable to those of transverse incisions.

1. McBurney’s Incisions:

These are specifically used for appendectomy (appendix removal operation). They are made at the junction of the middle third and outer third of the line running from the navel to the upper margin of the pelvic girdle.

2. Subcostal Incisions:

These start at the midline. They are 2-5 cm incisions below the lower part of the sternum (breastbone) that extends down outward parallel to the lower edge of the chest-rib. They provide easy access to the gallbladder and spleen. They are often performed in gallstone removal operations.

a. Kocher Incision:

A Kocher incision is a subcostal incision used to gain access for the gall bladder the biliary tree. The incision is made to run parallel to the costal margin, starting below the xiphoid and extending laterally.

The incision will then pass through the all the rectus sheath and rectus muscle, internal oblique and transversus abdominus, before passing through the transversalis fascia and then peritoneum to enter the abdominal cavity.

Structures within the transpyloric plane:

- L1 vertebral body

- Tip of the 9th costal cartilage

- Fundus of the gallbladder

- Duodeno-jejunal flexure

- Pylorus of the stomach

- The neck of the pancreas

- Renal hila

- Conus of the spinal cord

Two modifications and extensions of the Kocher incision are possible:

Chevron / Rooftop Incision or Modification:

The extension of the incision to the other side of the abdomen. This may be used for oesophagectomy, gastrectomy, bilateral adrenalectomy, hepatic resections, or liver transplantation

Mercedes Benz Incision or Modification:

The Chevron incision with a vertical incision and break through the xiphisternum. This may be used for the same indications as the Chevron incision, however classically seen in liver transplantation

b. Gridiron Incision:

An arcing incision through the skin, subcutaneous fat and fascia, external and internal obliques, transversus abdominis and transversalis fascia used for open appendicectomies.

The incision is centred over McBurney’s point two-thirds of the distance between the umbilicus and the right anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), where the base of the appendix is most likely to be found.

This classically corresponds to the area of maximal tenderness on clinical examination when the appendix has become sufficiently inflamed to cause localised peritonitis. This incision may be modified to follow the horizontal Langer’s lines for improved cosmesis.

Disadvantages include the risk of injury to the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. The arc may be extended cephalad and laterally in order to facilitate access to the ascending colon, which is known as the Rutherford-Morison incision.